ARM Push/Pop Stack Modes

In this article, we'll explore the stack modes, activities and accesses in ARM(A32/A64).

stack modes#

Arm Compiler armasm User Guide | 7. Writing A32/T32 Assembly Language - 7.16 Stack implementation using LDM and STM

You can use the LDM and STM instructions to implement pop and push operations respectively. You use a suffix to indicate the stack type.

The load and store multiple instructions can update the base register. For stack operations, the base register is usually the stack pointer, SP. This means that you can use these instructions to implement push and pop operations for any number of registers in a single instruction.

The load and store multiple instructions can be used with several types of stack:

Descending or ascending

The stack grows downwards, starting with a high address and progressing to a lower one (a descending stack), or upwards, starting from a low address and progressing to a higher address (an ascending stack).

Full or empty

The stack pointer can either point to the last item in the stack (a full stack), or the next free space on the stack (an empty stack).

suffixes#

To make it easier for the programmer, stack-oriented suffixes can be used instead of the increment or decrement, and before or after suffixes. The following table shows the stack-oriented suffixes and their equivalent addressing mode suffixes for load and store instructions:

Table 1. Stack-oriented suffixes and equivalent addressing mode suffixes

| Stack-oriented suffix | For store or push instructions | For load or pop instructions |

|---|---|---|

| FD (Full Descending stack) | DB (Decrement Before) | IA (Increment After) |

| FA (Full Ascending stack) | IB (Increment Before) | DA (Decrement After) |

| ED (Empty Descending stack) | DA (Decrement After) | IB (Increment Before) |

| EA (Empty Ascending stack) | IA (Increment After) | DB (Decrement Before) |

The following table shows the load and store multiple instructions with the stack-oriented suffixes for the various stack types:

Table 2. Suffixes for load and store multiple instructions

| Stack type | Store | Load |

|---|---|---|

| Full descending | STMFD (STMDB, Decrement Before) |

LDMFD (LDM, increment after) |

| Full ascending | STMFA (STMIB, Increment Before) |

LDMFA (LDMDA, Decrement After) |

| Empty descending | STMED (STMDA, Decrement After) |

LDMED (LDMIB, Increment Before) |

| Empty ascending | STMEA (STM, increment after) |

LDMEA (LDMDB, Decrement Before) |

Full Ascending:

- STMIB, STMFA: Store Multiple Increment Before (Full Ascending)

- LDMDA, LDMFA: Load Multiple Decrement After (Full Ascending)

Empty Descending:

- STMDA, STMED: Store Multiple Decrement After (Empty Descending)

- LDMIB, LDMED: Load Multiple Increment Before (Empty Descending)

Empty Ascending:

- STM, STMIA, STMEA: Store Multiple (Increment After, Empty Ascending)

- LDMDB, LDMEA: Load Multiple Decrement Before (Empty Ascending)

default(FD)#

The Procedure Call Standard for the Arm Architecture (AAPCS), and armclang always use a full descending stack.

The PUSH and POP instructions assume a full descending stack. They are the preferred synonyms for STMDB and LDM with writeback.

Push: decrement sp then put item on stack – pre-decrement, e.g. stmfd. STMDB, STMFD: Store Multiple Decrement Before (Full Descending).

Store Multiple Decrement Before (Full Descending) stores multiple registers to consecutive memory locations using an address from a base register. The consecutive memory locations end just below this address, and the address of the first of those locations can optionally be written back to the base register.

Pop: copy item from stack then increment sp – post-increment, e.g. ldmfd. LDM, LDMIA, LDMFD: Load Multiple (Increment After, Full Descending).

Load Multiple (Increment After, Full Descending) loads multiple registers from consecutive memory locations using an address from a base register. The consecutive memory locations start at this address, and the address just above the highest of those locations can optionally be written back to the base register.

For example:

STMFD sp!, {r0-r5} ; Push onto a Full Descending Stack

LDMFD sp!, {r0-r5} ; Pop from a Full Descending Stack

PUSH/POP#

PUSH (single register): an alias of STR (immediate)

It's equivalent to STR{<c>}{<q>} <Rt>, [SP, #-4]!and is always the preferred disassembly.

PUSH: Push Multiple Registers to Stack - PUSH (multiple registers): an alias of STMDB, STMFD

Push Multiple Registers to Stack stores multiple general-purpose registers to the stack, storing to consecutive memory locations ending just below the address in SP, and updates SP to point to the start of the stored data.

The lowest-numbered register is stored to the lowest memory address, through to the highest-numbered register to the highest memory address. See also Encoding of lists of general-purpose registers and the PC.

POP (single register): an alias of LDR (immediate)

It's equivalent to LDR{<c>}{<q>} <Rt>, [SP], #4 and is always the preferred disassembly.

POP: Pop Multiple Registers from Stack - POP (multiple registers): an alias of LDM, LDMIA, LDMFD

Pop Multiple Registers from Stack loads multiple general-purpose registers from the stack, loading from consecutive memory locations starting at the address in SP, and updates SP to point just above the loaded data.

The lowest-numbered register is loaded from the lowest memory address, through to the highest-numbered register from the highest memory address. See also Encoding of lists of general-purpose registers and the PC.

The push and pop operations are store many and load many op codes, the assumption being that a function will need to save and restore the contents of several registers that it is likely to corrupt (of course it is possible to deal with just one register!).

When a list of registers is given the lowest numbered register uses the lowest stack memory location and the highest numbered register uses the highest stack memory location. This is true no matter what order we specify the registers!

The important thing is to remember whether the stack pointer is altered pre- or post- before the multiple registers are dealt with!

aapcs64 stack#

aapcs64 | 6 The Base Procedure Call Standard - 6.4 Memory and the Stack - 6.4.5 The Stack

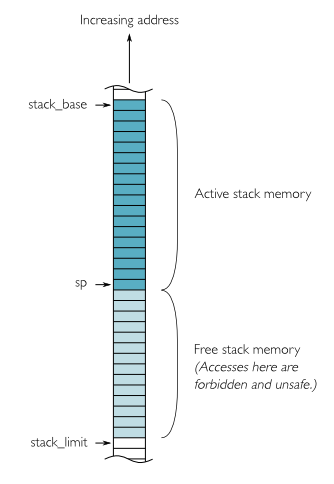

Each thread has a stack. This stack is a contiguous area of memory that the thread may use for storage of local variables and for passing additional arguments to subroutines when there are insufficient argument registers available.

The stack is defined in terms of three values:

- a base (Lbound?)

- a limit (Ubound?)

- the current stack extent, stored in the special-purpose register

SP(armasm-ref-guide, Programmer's Guide)

activity#

The SP moves from the base to the limit as the stack grows, and from the limit to the base as the stack shrinks. In practice, an application might not be able to determine the value of either the base or the limit.

In the description below, the base, limit, and current stack extent for a thread T are denoted T.base, T.limit, and T.SP respectively.

The stack implementation is full-descending(FD), so that for each thread T:

- \(T.limit < T.base\) and the stack occupies the area of memory delimited by the half-open internal \([T.limit, T.base)\).

- The active region of T's stack is the area of memory delimited by the half-open interval \([T.SP, T.base)\). The active region is (initial) empty when T.SP is equal to T.base.

- The inactive region of T's stack is the area of memory denoted by the half-open interval \([T.limit, T.SP)\). The inactive region is empty when T.SP is equal to T.limit.

The stack may have a fixed size or be dynamically extendable (by adjusting the stack-limit downwards, towards lower addresses).

The rules for maintenance of the stack are divided into two parts: a set of constraints that must be observed at all times, and an additional constraint that must be observed at a public interface.

constraints#

At public interfaces, the alignment of stack-pointer(sp) must be two times the pointer size.

For AArch32 that's 8 bytes, and for AArch64 it's 16 bytes.

For AArch32 (ARM or Thumb), sp must be at least 4-byte aligned at all times.

For AArch64, sp must be 16-byte aligned whenever it is used to access memory.

6.4.5.1 Universal stack constraints

At all times during the execution of a thread T, the following basic constraints must hold for its stack S:

-

\(T.limit ≤ T.SP ≤ T.base\). T's stack pointer must lie within the extent of the memory occupied by S.

-

No thread is permitted to access (for reading or for writing) the inactive region of S.

-

If MTE is enabled, then the tag stored in

T.SPmust match the tag set on the inactive region of S.

Additionally, at any point at which memory is accessed via SP, the hardware requires that

- \(SP\ mod\ 16 = 0\). The stack must be quad-word aligned.

6.4.5.2 Stack constraints at a public interface

The stack must also conform to the following constraint at a public interface:

- \(SP\ mod\ 16 = 0\). The stack must be quad-word aligned.

Frame Pointer#

6.4.6 The Frame Pointer

Conforming code shall construct a linked list of stack-frames. Each frame shall link to the frame of its caller by means of a frame record of two 64-bit values on the stack (independent of the data model). The frame record for the innermost frame (belonging to the most recent routine invocation) shall be pointed to by the frame pointer register (FP, X29 in AArch64). The lowest addressed double-word shall point to the previous frame record and the highest(next to FP?) addressed double-word shall contain the value passed in LR(X30 in AArch64) on entry to the current function. If code uses the pointer signing extension to sign return addresses, the value in LR must be signed before storing it in the frame record. The end of the frame record chain is indicated by the address zero in the address for the previous frame. The location of the frame record within a stack frame is not specified.

sp sem break moment

There will always be a short period during construction or destruction of each frame record during which the frame pointer will point to the caller's record.

A platform shall mandate the minimum level of conformance with respect to the maintenance of frame records. The options are, in decreasing level of functionality:

-

It may require the frame pointer to address a valid frame record at all times, except that small subroutines which do not modify the link register may elect not to create a frame record

-

It may require the frame pointer to address a valid frame record at all times, except that any subroutine may elect not to create a frame record

-

It may permit the frame pointer register to be used as a general-purpose callee-saved register, but provide a platform-specific mechanism for external agents to reliably detect this condition

-

It may elect not to maintain a frame chain and to use the frame pointer register as a general-purpose callee-saved register.

stack equiv#

Functions and the Stack#

Programming with 64-Bit ARM Assembly Language | Chapter 6: Functions and the Stack

In this chapter, we will examine how to organize our code into small independent units called functions. This allows us to build reusable components, which we can call easily form anywhere we wish by setting up parameters and calling them.

Typically, in software development, we start with low-level components. Then we build on these to create higher- and higher-level modules. So far, we know how to loop, perform conditional logic, and perform some arithmetic. Now, we examine how to compartmentalize code into building blocks.

We introduce the stack, a computer science data structure for storing data. If we're going to build useful reusable functions, we need a good way to manage register usage, so that all these functions don't clobber each other. In Chapter 5, “Thanks for the Memories,” we studied how to store data in a data segment in main memory. The problem with this is that this memory exists for the duration that the program runs. With small functions, like converting to upper-case, they run quickly; thus they might need a few memory locations while they run, but when they're done, they don't need this memory anymore. Stacks provide us a tool to manage register usage across function calls and a tool to provide memory to functions for the duration of their invocation.

We introduce several low-level concepts first, and then we put them all together to effectively create and use functions. First up is the abstract data type called a stack that is a convenient mechanism to store data for the duration of a function call.

Stacks work great for saving and restoring registers, but to work well for other data, we need the concept of a stack frame. Here we allocate a block or frame of memory on the stack that we use to store our variables. This is an efficient mechanism to allocate some memory at the start of a function and then release it before we return.

PUSHing variables on the stack isn't practical, since we need to access them in a random order, rather than the strict LIFO protocol that PUSH/POP enforce.

implementation#

For AArch64, sp must be 16-byte aligned whenever it is used to access memory. This is enforced by AArch64 hardware.

- This means that it is difficult to implement a generic

pushorpopoperation for AArch64. There are nopushorpopaliases like there are for ARM and Thumb. - The hardware checks can be disabled by privileged code, but they're enabled in at least Linux and Android.

The alignment-check-on-memory-access means that AArch64 cannot have general-purpose push- or pop-like operations.

If you're dealing with hand-written AArch64 assembly code, you'll have to be aware of these limitation. Whenever the stack pointer is used as the base register in an address operand, it must have 16-byte alignment.

To allocate space on the stack, we use a subtract instruction to grow the stack by the amount we need.

// Broken AArch64 implementation of `push {x1}; push {x0};`.

str x1, [sp, #-8]! // This works, but leaves `sp` with 8-byte alignment ...

str x0, [sp, #-8]! // ... so the second `str` will fail.

In this particular case, the stores could be combined:

The STP instruction moves the stack pointer down by 16 bytes, providing us a region of memory on the stack to place the variables.

However, in a simple compiler, it is not always easy to combine instructions in that way.

The alignment checks can be very inconvenient in code generators where it is not feasible to determine how much stack space a function will require. Many JIT compilers fall into this category; they tend to rely on being able to push individual values to the stack.

- Calculate stack sizes in advance

- Use 16-byte stack slots

-

Use a register other than

spas the stack pointer- Separate stack area

- Reserve stack space in advance

- Shadow

sp

Before the end of the function, we need to execute

to release our variables from the stack. Remember, it is the responsibility of a function to restore SP to its original state before returning.

prolog/epilog#

Arm Compiler armasm User Guide | 7. Writing A32/T32 Assembly Language - 7.17 Stack operations for nested subroutines

Arm Assembly Internals and Reverse Engineering | Chapter 8 Control Flow - Functions and Subroutines - Leaf and Nonleaf Functions

Stack operations can be very useful at subroutine entry and exit to avoid losing register contents if other subroutines are called.

At the start of a subroutine, any working registers required can be stored on the stack, and at exit they can be popped off again.

In addition, if the link register is pushed onto the stack at entry, additional subroutine calls can be made safely without causing the return address to be lost. If you do this, you can also return from a subroutine by popping the PC off the stack at exit, instead of popping the LR and then moving that value into the PC. For example:

subroutine PUSH {r5-r7,lr} ; Push work registers and lr

; code

BL somewhere_else

; code

POP {r5-r7,pc} ; Pop work registers and pc

The prologue of a function starts by pushing the register values it is going to modify but is required to preserve onto the stack. It adjusts the SP to make room for local variables and updates the frame pointer register for the current stack frame.

One of the register values that nonleaf functions push onto the stack at the beginning of the prologue is the LR, since it will be overwritten when another subroutine is called. This value is then restored to the PC in the function epilogue.

Depending on the implementation of the platform, the Frame Pointer (FP/R29) is used to keep track of the current stack frame and must be preserved as well.

The following snippet is a typical prolog/prelude and epilog/postlude of a subroutine disassembly.

// pwndbg> disassemble main

// prolog/prelude

0x00000000004008e0 <+0>: stp x29, x30, [sp, #-48]!

0x00000000004008e4 <+4>: mov x29, sp

[...armasm...]

// epilog/postlude

0x000000000040094c <+108>: ldp x29, x30, [sp], #48

0x0000000000400950 <+112>: ret

stp x29, x30, [sp, #-48]!:

- \(sp \mathrel{-}= 48\): stack grows downwards with size=0x30, 16-byte aligned.

-

push FP & LR to stack [sp], [sp+8]

r2 expr of prolog

dr sp=`dr sp`-0x30

wvp `dr x29` @ sp; wvp `dr x30` @ sp+8

Note: The SP remains the same as the X29/FP throughout the subroutine. The FP is not used and the SP is only used as a base register.

gcc -fomit-frame-poiter

If we explicitly indicate that we do not need BP/FP to provide stack frame information, the compiler can omit the actions of saving BP/FP after entering the procedure and restoring BP/FP before exiting the procedure, and use SP directly to address the parameters and internal variables of the procedure.

For the sake of pursuing higher performance, for example, when compiling the Linux kernel, you will find that the internal function is indeed addressed directly by SP.

For gcc and g++, you can use the -fomit-frame-poiter compilation option to instruct gcc to use SP addressing directly.

Omit the frame pointer in functions that don't need one. This avoids the instructions to save, set up and restore the frame pointer; on many targets it also makes an extra register available.

On some targets this flag has no effect because the standard calling sequence always uses a frame pointer, so it cannot be omitted.

ldp x29, x30, [sp], #48:

- pop FP & LR from stack [sp], [sp+8]

-

\(sp \mathrel{+}= 48\): stack shrinks backward

r2 expr of epilog

dr x29=pv@sp; dr x30=pv@sp+8

dr sp=`dr sp`+0x30

ret(RET {Xn}): Return from subroutine

- Branches unconditionally to an address in a register.

- Defaults to

X30(LR) if absent.

refs#

ABI & Calling conventions

Register file of ARM64

Stacks on ARM processors

Using the Stack in AArch32 and AArch64

Using the Stack in AArch64: Implementing Push and Pop